Social Neural Networks

As Ralph Adolphs and Daniel Kennedy claim “the social brain, and its dysfunction and recovery, must be understood not in terms of specific structures, but rather in terms of their interaction in large-scale networks” and that “no social process can be attributed to a single structure alone; instead a network view of brain function is required” (Kennedy, Adolphs, 2012, 559–572/1).

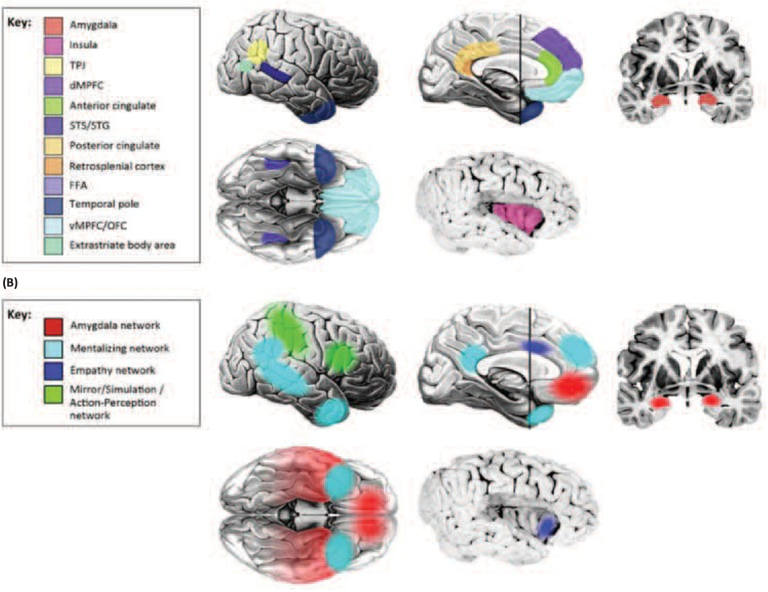

To identify brain regions implicated in social behavior, Daniel Kennedy and Ralph Adolphs (2012) reviewed lesion studies of brain-injured patients and fMRI activation in healthy participants. Part A in the following figure lists individual cerebral structures implicated in social behavior, and part B demarks four social-related brain networks that tie these regions together:

- Amygdala network. It includes the orbitofrontal cortex, the temporal cortex and the amygdala. The functions of this network range from triggering emotional responses to detecting socially relevant stimuli.

The important role of the amygdala in social network construction and maintenance has also been confirmed by Jones et al. (2020). According to the authors, the amygdala is presumed to track visual signals in social interactions, such as face stimuli, gestures, and expressions (Bickart et al, 2011, 2012). A larger amygdala provides an individual with advantages in processing non-verbal social signals (Bickart et al, 2011, 2012).

In addition, the amygdala tracks the reward value brought by social interaction. Individuals with a larger volume, higher gray matter density, or higher activation level of the amygdala tend to perceive social interaction as more interesting and of higher reward value, which in turn prompts them to develop more social connections (Bickart et al, 2012; Zerubavel et al, 2015; Liu et al, 2019).

The functional connectivity between the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is crucial for facial expression recognition, social strategy development, social reward processing, prosocial behavior, etc. (Hampton et al, 2016; Kwak et al, 2018). Researchers generally agree that amygdala-OFC functional connectivity stably and positively predicts the differences in social network size among individuals (Hampton et al, 2016; Kwak et al, 2018).

Another non-verbal stimulus, having impact on amygdala network is smell – it is a type of social signal that conveys information about an individual, such as sex, disease and emotional state; therefore, individuals with high olfactory sensitivity are able to identify social signals from the body odor of others, which is conductive to social interaction (Zou et al, 2016). (Han, 2021).

- Mentalizing network. This collection of structures related to thinking about the internal states of others includes the support temporal sulcus and anterior temporal cortex, providing a mechanism for understanding others’ actions.

Mentalizing is a term sometimes used interchangeably with theory of mind (ToM), both typically refer to the cognitive processes involved in understanding the intentions, desires, or beliefs of another person. The “mentalizing network” involves brain regions that have been shown to be activated when someone thinks about another person’s mental states. (Kilroy, Aziz-Zadeh, 2017)

Mentalizing enables the ability to empathize and cooperate with others, accurately interpret other people’s behavior, and even deceive others when necessary (Mitchell, J., Heatherton, T., 2009: 955).

Individuals with larger OFC (orbitofrontal cortex) volumes have higher mentalizing competence and thus more complex social relations (Powell et al., 2012).

The PFC is the core brain region in the mentalizing network. The vmPFC (ventromedial prefrontal cortex) and OFC are involved in the emotional part of the theory of mind and are mainly responsible for understanding the emotional state of others (Abu-Akel, Shamay-Tsoory, 2011) (Han et al, 2021).

- Empathy network. Structures involved when individuals empathize with others include the insula and cingulate cortex. The empathy network can attribute intentions to others, something we humans do automatically. Indeed, humans seem compelled to attribute intentions and other psychological motives even to nonhumans and abstract animations.

One of the important roles of the AIC (anterior insular cortex) is to process interpersonal emotional information, including sympathy, empathy and understanding the feelings of others (Pillemer et al, 2017; Spagna et al, 2018). (Han et al, 2021).

- Mirror/stimulation/action – perception network. Activated when observing the actions of others, this network includes the mirror neuron systems of the parietal and premotor cortex (detailed in Figure B) and is also thought to be involved in developing our concept of self. (Kolb, Whishaw, 2007, 569-70)

The mirror neuron system is mainly responsible for supporting imitation and understanding other people’s actions (Ikeda et al., 2019). Brain regions such as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), inferior parietal lobule (IPL), and STS are involved in the mirror neuron system.

The pSTS (posterior superior temporal sulcus) is specialized for understanding and imitating the non-verbal social signals of others, such as body movements, eye gaze, and mouth movements (Deen, Saxe, 2019).