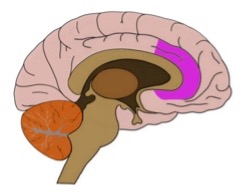

Executive attention network

The executive attention network determines how the selected task-relevant information is processed (Posner, 2012:72-97). Sometimes, it is also called “concentration” or “self-regulation”. In cognitive neuroscience, this system is called the cognitive control system (Gazzaniga, 2019:516ff). This system heavily relies on regions in the prefrontal cortex and their connectivity to the rest of the brain. From a developmental perspective, the prefrontal cortex is the last part of the brain to mature (Casey et al., 2005). On average, the prefrontal cortex reaches full maturity between the ages of 22-25.

The executive attention network provides top-down control over behaviour and thoughts. It can be compared to a railroad yardman, who orients the switches in the proper position, so each train arrives at the right track (Dehaene; 2020:159). Or in other words, the executive attention network decides how the attended information is processed based on the current goal we want to achieve. Some tasks of the executive attention network:

- making a plan of action

- selecting task-relevant information

- inhibiting distractions

- initiating action

- monitoring behaviour and keeping it on track

- switching strategies (if the ones chosen do not work out)

Two regions are of importance in the prefrontal cortex:

However, there is an important caveat: working memory cannot hold two different tasks active simultaneously (Cognitive Load Theory; Sweller, 1988). So multitasking is impossible. In so-called “multitasking”, the brain quickly switches between task A and task B. But this switching comes at a cost: it costs more energy (task-switching costs), and more mistakes are made. If you want to take this to the test: task A: say the alphabet; task B count to 26; now switch between task A and task B: A 1, B 2, C 3, D 4, …

The executive attention network is responsible for one of the essential skills that students can and must develop. As a teacher, you can support this development by providing learning opportunities in which they learn to self-control, concentrate, monitor their learning progress, and, if necessary, adjust their ongoing learning process.

We cannot expect a child or and adult to learn two things at once. Teaching requires paying attention to the limits of attention, and therefore, carefully prioritizing specific tasks. Any distraction slows down or wastes our efforts: if we try to do several things at once, our central executive quickly loses track.

– Dehaene (2020:162)

Thus, the available primary data do not support the concept of a 10- to 15-min attention limit. Interestingly, the most consistent finding from a literature review is that the greatest variability in student attention arises from differences between teachers and not from the teaching format itself.

– Bradbury (2016:149)

If you want to read more:

- De Haan, M. (2013). Attention and executive control. In: Mareschal, D., Butterworth, B., & Tolmie, A., Educational neuroscience, 325-348.

- Dehaene, S. (2020). How we learn: The new science of education and the brain. Penguin UK, 147-175

- Posner, M. I. (2012). Attention in a social world. Oxford University Press.

- Ward, J. (2020). The student’s guide to cognitive neuroscience (Fourth edition), 203-231.

Quiz Summary

0 of 2 Questions completed

Questions:

Information

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading…

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You must first complete the following:

Results

Results

0 of 2 Questions answered correctly

Your time:

Time has elapsed

You have reached 0 of 0 point(s), (0)

Earned Point(s): 0 of 0, (0)

0 Essay(s) Pending (Possible Point(s): 0)

Categories

- Not categorized 0%

- 1

- 2

- Current

- Review

- Answered

- Correct

- Incorrect

-

Question 1 of 2

1. Question

1. The executive attention network is also called: …

CorrectIncorrect -

Question 2 of 2

2. Question

2. Fill in the missing words: current goal, top-down-control, behaviour and thoughts, processed, how

-

The executive attention network provides over . Or in other words, this network decides the attended information is based on the we want to achieve.

CorrectIncorrect -